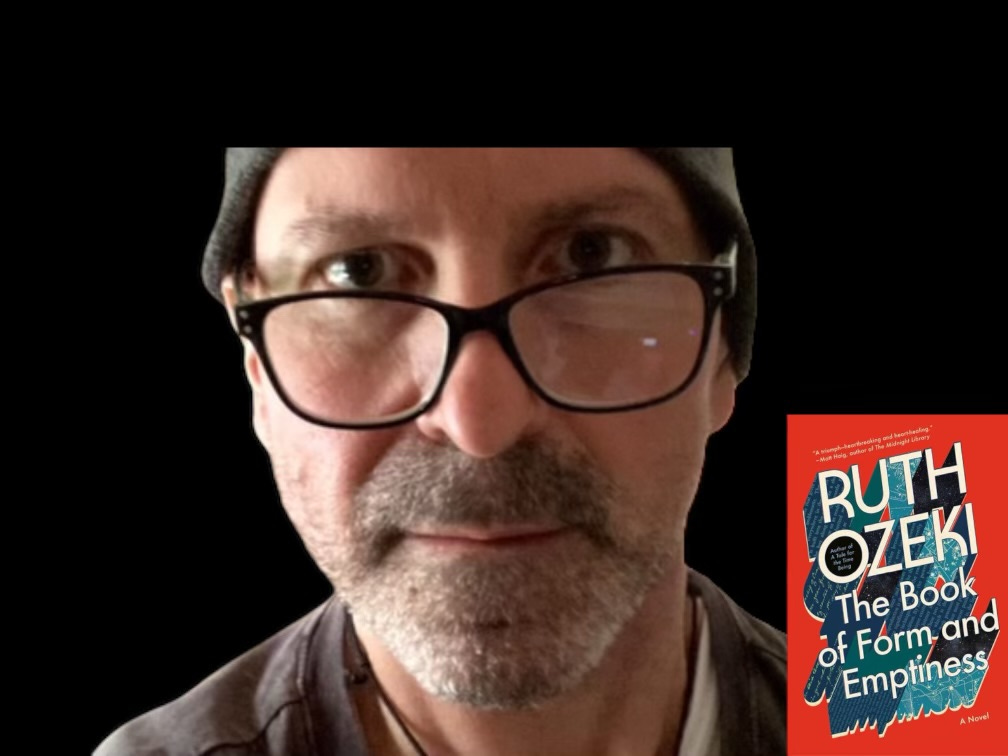

Kert Lenseigne, who I met via the Substack community, feels like a true soul brotha. A husband, father, Zen student, soul advocate, and guardian of human possibility, Kert, like me, gets his jollies out of engaging deeply with the existential questions that life throws our way.

His Substack Digital publication, “Alchemy of a Journey,” delves into what he describes as "On Becoming through the five dimensions of being human," exploring what it means to be a spiritual being on a human journey.

So it’s no surprise that Kert was drawn to Ruth Ozeki’s “The Book of Form and Emptiness,” a novel that speaks directly to those pondering the soul, loss, and the material world.

Ozeki, herself a Zen priest, crafts a story that is at once about a boy hearing the voices of inanimate objects and about the deeper nature of reality and existence.

The Soul of Objects and the Voices We Hear

Kert Lenseigne appears to understand soul work in a way that aligns perfectly with the themes in “The Book of Form and Emptiness.” The novel introduces us to Benny Oh, a boy who starts hearing the voices of objects around him following the death of his father.

This narrative allows us to imagine what it’s like to be thrust into a world where even a sneaker or a wilted lettuce leaf communicates with you. For Kert, this is more than a story gimmick—it mirrors his belief that “all Beings (even the more-than-human ones) have Soul.”

It’s here where Kert acknowledges that everything, from stones to his iPad, carry a certain weight, a presence that Western language struggles to describe without anthropomorphizing.

This concept resonates deeply with Kert’s spiritual philosophy, one shaped by Zen teachings and influenced by the poetic wisdom of Thich Nhat Hanh: "We inter-are."

He believes that we don't just co-exist with other humans; we co-exist with everything. For Kert, the world is alive in ways many of us fail to notice, partly because we’ve forgotten how to listen. It’s here that Benny’s journey as explored in the book is, therefore, a universal metaphor for our spiritual deafness and the urgent need to reclaim a more profound way of being.

Zen, Grief, and the Messiness of Family

Kert’s experience as a grief advocate and former caregiver for his father who succumbed to dementia and Parkinson's gives him a unique perspective on the family dynamics in Ozeki’s novel.

Benny's mother, Annabelle, deals with her grief by hoarding, clinging to material possessions to fill the void left by her husband's death. Annabelle's compulsion to hoard is both a coping mechanism and a cry for help, misunderstood by those around her—including her son.

Kert sees a profound lesson here: “We judge others by their actions; we judge ourselves by our intentions.”

Ozeki’s narrative brilliantly captures the complexities of family trauma and healing, a topic Kert is no stranger to. He says that his journey from Catholicism to Zen Buddhism, from atheist altar boy to a “beginner’s mind” Taoist, is a reflection of his own dance with the shadows of grief and trauma. He knows well that healing is not linear; it spirals, overlaps, and often leads us to strange sanctuaries.

In Benny’s case, it’s the library—a sacred space where voices are quieter, where souls on different journeys intersect.

The Library as Sacred Space: Finding Refuge Among Books and Souls

Kert’s reflections on the library as a place of sanctuary resonate with his own experiences. He describes libraries much like cathedrals or zendos—spaces that naturally inspire reverence and slow, mindful movement.

He also has an affinity for bookstores, especially those with cafés, which he says serve a similar sacred function. He speaks of Third Place Books in Seattle as a favorite “third place,” a spiritual and sensory refuge where oat milk lattes mingle with the smell of freshly printed pages.

It’s here where Kert’s attachment to books, similar to Annabelle’s, runs deep. He can’t bear to part with them, turning his home into a sanctuary of bound pages.

Kert’s reflection on libraries also speaks to his broader belief in the importance of places outside of home and work where one can exist authentically, encounter diversity, and grow. Just as Benny finds solace in the library among eccentric characters like a street artist and a homeless philosopher-poet, Kert finds refuge and growth in the "wildness" of his acre of land in Washington state or in the sacred, diverse ecosystem of a school.

Ruth Ozeki, author of “The Book of Form and Emptiness” is a novelist, documentary filmmaker, teacher, and Zen Buddhist priest.

Form and Emptiness: The Book as Both Object and Guide

In “The Book of Form and Emptiness,” the proverbial "Book" itself becomes a character, guiding Benny through his tumultuous inner and outer worlds. Kert describes the “Book” as not merely a narrative device; it is a spiritual companion—a "finger pointing at the moon," helping us see the subtleties of form and emptiness.

The Book is less about what it says and more about what it invites us to feel and experience, echoing Kert’s own philosophical and Zen leanings.

Kert’s reflections to me about this book felt like a meditation—a conversation with Ozeki’s text that flows between the philosophical, the spiritual, and the personal. He seems to understand that to engage deeply with a novel like this is to engage with oneself.

The Book asks Benny, and by extension, the reader, to listen, not just to the voices of objects but to the unmanifested emotions within and around us. “All emotions are present at every moment in their unmanifest form," says Ram Dass, another of Kert's influences.

“The Book of Form and Emptiness” is not just about understanding the spoken word; it’s about attuning ourselves to the silence that gives rise to words.

The Alchemy of Reading and Becoming

For Kert, reading “The Book of Form and Emptiness” reflects an act of alchemy, transforming the mundane into the sacred, the material into the spiritual. His journey with the book mirrors his journey with life—a Zen walk that acknowledges both form and emptiness, understanding that each informs and shapes the other.

Ruth Ozeki’s novel is not merely a story; it is a koan, a spiritual riddle that invites us to embrace the messiness of our lives, to listen deeply to the world around us, and to find stillness in the chaos.

What a surprise to see Kert here, and what a unique way to collaborate, Diamond-Michael. Nice work! I really enjoyed Ozeki's book A Tale for the Time Being, which takes place in a Zen monastery, and I have this one on my list. Thanks to both of you!

Great post. Thanks to you both. Kert, the spookiness continues - I love Ruth Ozeki’s novels and have read this one and A Tale for the Time Being numerous times. Plus Ram Dass also a great inspiration! I am writing about him soon!