When Zhuangzi Met Joseph Campbell

A Hypothetical Taoist Take on the Hero’s Journey (With a Side of Ayn Rand’s Ego)

I can only imagine the lively exchange that would take place if the acclaimed mythologist Joseph Campbell and the Taoist sage Zhuangzi sat down for tea.

The breeze might carry the scent of wildflowers while these two spiritual adventurers, separated by millennia and culture, discuss the “Hero’s Journey.” Campbell, armed with his iconic book “Hero with a Thousand Faces,” would wax lyrical about the universal monomyth, the narrative arc that frames countless myths across the world: a call to adventure, trials, victories, and a return home, transformed, and ready to share newfound wisdom.

Meanwhile, Zhuangzi, in his humble robe and with a cricket’s chuckle, might gently wave his hand, questioning why anyone would bother leaving their comfy perch when the Great Way is ever-present, laughing at the absurdity of chasing after anything in particular.

As a longtime explorer of Taoism and admirer of Campbell’s work, I often find myself imagining how the philosophical flow of Zhuangzi's effortless wandering might intersect with Campbell’s structured heroic arc. I’ve read “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” many times, and each journey through its pages has prompted a different reflection, a different resonance in the river of my thoughts.

Campbell’s central premise is seductive: the hero’s journey is an ancient pattern—a blueprint encoded in our collective psyche. We leave home (literally or metaphorically), face challenges, defeat monsters, uncover truths, and return changed.

The purpose of this journey? To enrich not just ourselves but our community; to bring back a gift, some hard-won boon that serves others.

With this, there’s an underlying ethos of self-sacrifice and transformation that, in many ways, mirrors certain Taoist ideas—just not in the straightforward, dramatic manner of Campbell’s mythic heroes.

Zhuangzi, with his love of paradox and irony, would likely raise an eyebrow at the notion of “the hero.” Where Campbell finds nobility in the quest, Zhuangzi might see folly. “Why strive and strain when the Dao flows freely, unperturbed by human ambition?” Zhuangzi might say with a grin.

In his tales, the sage and the butcher are equally heroic, precisely because they don’t see themselves as heroes. In fact, they aren’t even concerned with success or failure, victory or loss. The real “journey” is in forgetting there is a journey at all—allowing yourself to be carried by the current, letting things be as they are.

Here’s where I see the interesting tension between Campbell’s magnum opus “Hero with a Thousand Faces” and Taoist philosophy. Campbell’s hero is a doer—a deliberate seeker of the sacred boon. But like me, Zhuangzi’s sage, by contrast, is a being—a drifter, a wanderer who finds value in embracing the spontaneous unfolding of life without grasping, without setting out to achieve anything in particular.

I’ve often wondered how much of Campbell’s hero’s journey is a reflection of the Western obsession with striving and achievement, wrapped in the narrative structures we so love.

The Taoist “journey,” if we can even call it that, is more circular and less goal-oriented. It’s about arriving without departing, achieving without effort.

As I think more on it, Campbell’s mythic structure might itself be seen as a cultural artifact—a lens we’ve built to give our messy lives meaning and purpose. Zhuangzi would likely smile, seeing it all as one big cosmic joke.

But let’s add Ayn Rand to the tea party, shall we? Her ideas about radical individualism, as presented in “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged,” seem at first to be in stark contrast with both Campbell’s communal ethos and Zhuangzi’s Taoist nonchalance.

Rand’s heroes—Howard Roark, John Galt—aren’t on a journey to serve anyone but themselves. Her philosophy of Objectivism prizes ego above all, asserting that self-interest is the ultimate good and that altruism is akin to self-destruction.

In this context, Rand’s heroes appear more like anti-Campbells, rejecting the notion that the hero’s journey is about returning to serve the community. To her, the “boon” isn’t a gift for others but a triumph of the self.

Zhuangzi, who warned against such rigid dogmas and fixed beliefs, might find Rand’s staunch individualism amusingly misguided, another example of someone boxing themselves in with their own ideas. “Just let go of your ego,” Zhuangzi might say, shaking his head at Roark’s architectural obsession, “and maybe you’ll design a building that floats like a cloud.”

Yet, in the midst of these contrasts, there’s a curious intersection. Both Rand and Zhuangzi, for all their differences, advocate for authenticity and self-knowledge—albeit for vastly different reasons.

Rand’s heroes seek an authentic self that is gloriously independent, while Zhuangzi’s sage seeks an authentic self that is boundless, ungraspable, and connected to the flow of the Tao. It’s here that I find myself reflecting on how Campbell’s hero, too, is in search of authenticity—one that’s discovered through challenge, suffering, and ultimately, surrender.

In the end, whether one is a Campbellian hero setting out on an epic quest, a Taoist sage lounging by the river, or a Randian architect drawing skyscrapers in defiance of the world, the dance remains the same: a movement between self and the universe, between the ego and something larger. The difference lies in how one chooses to approach that dance—grasping, releasing, or simply wandering.

So what would Campbell, Zhuangzi, and Rand teach us over tea? Perhaps that the most meaningful journey is one where we find the courage to let go of our carefully crafted stories, our desperate striving, and our need to control the narrative.

Whether you’re setting out to slay dragons, build skyscrapers, or drift with the Tao, the wisdom lies in understanding that the hero’s journey isn’t really about getting anywhere. It’s about allowing life to unfold, serving others when called, and laughing at the absurdity of it all when the tea finally goes cold.

In the words of Zhuangzi: “The true man of Tao forgets the road he travels, as if he’s simply been blown along like a leaf in the wind.”

And maybe that’s the hero’s journey after all—not a straight line, but a meandering flow back into the vast, laughing void where all faces, heroes and fools alike, are ultimately one.

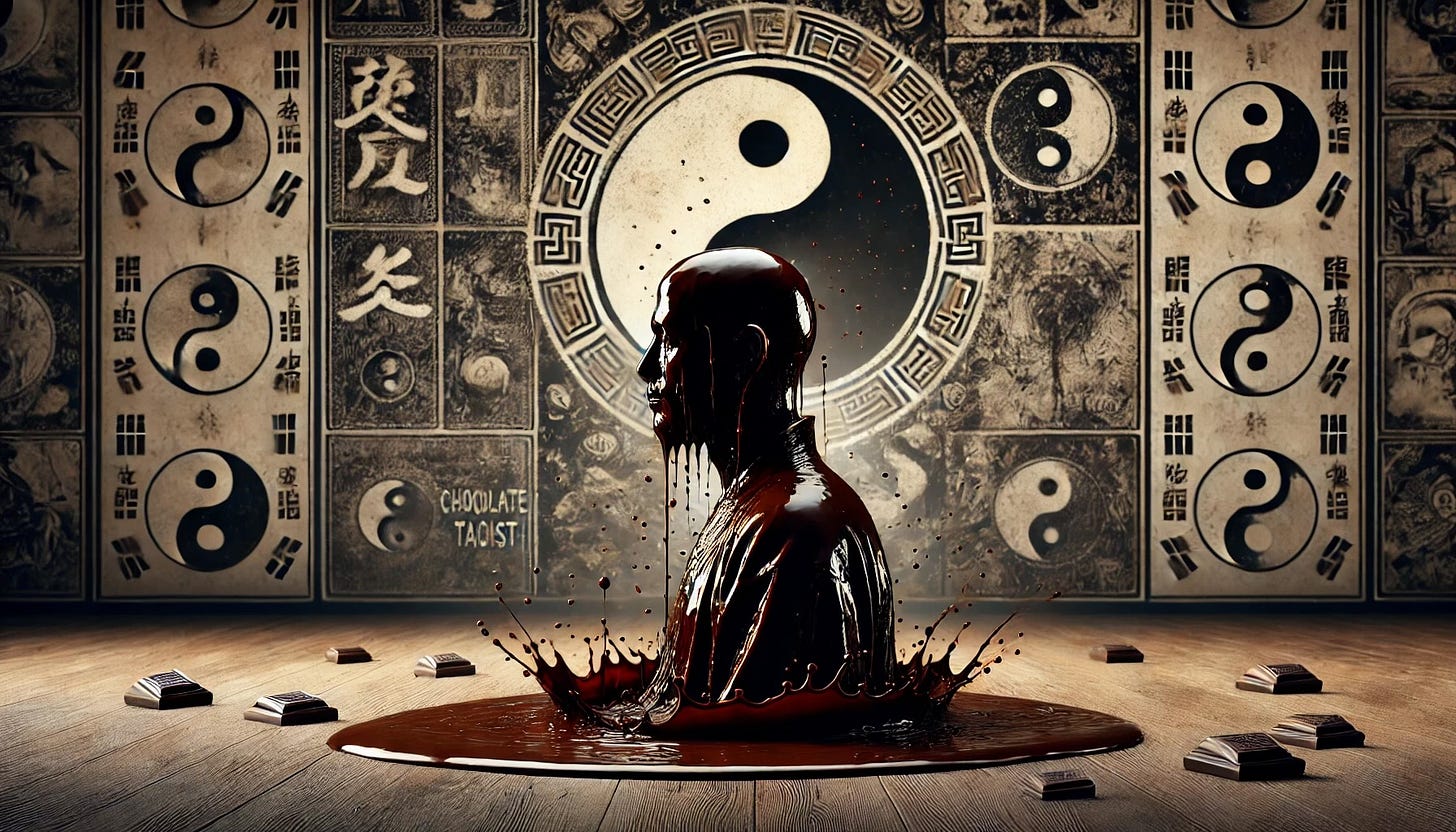

If this publication has been a source of wisdom for you then please consider helping me sustain it by becoming a monthly or annual contributor.

For just $6.00/month or $60.00/year, you’ll have the opportunity to share your lived experiences with fellow nomads, fueling fiery discussions that provoke, inspire, and challenge you to think differently.

So I hope you will take the plunge today and contribute to my mission of helping human travelers on this life journey.

Onward and Forward

Diamond Michael Scott aka The Chocolate Taoist

“I’ve often wondered how much of Campbell’s hero’s Journey is a reflection of the western obsession of striving and achievement wrapped in the narrative structures we so love.” I bought a copy of the heroes Journey a couple of summers ago, expecting to be enthralled once again and found myself disappointed. I think precisely by the thing that you are reflecting on just now. Ultimately, it is in surrender, though, isn’t it—whether we’re coming from Ayn Rand’s perspective of the egoic self or the journey that leads us to the greater realization of big ass ELF (Self) or the meandering stream that finds peace in not having to or needing to control the narrative. I think what you’ve written here is of major importance— if only in the moment to little me I think it’s ingenious the way you’ve woven these three entities chatting over tea.

Great topic. Great treatment!