For me, I find that there’s something wild and poetic that happens when two seemingly distant cultures meet, not in conquest or commerce, but in the quiet realms of thought, spirit, and resistance.

That’s the terrain I’ve been reflecting on lately: the overlapping dance between Black American culture and Chinese philosophy. The more I examine this duality, the more I see not a collision, but a current. A flow. A coded language of harmony, suffering, and transcendent wisdom passed down like a knowing glance across oceans and centuries.

As Black Americans, our struggle has always been not just political but existential. Here, we pose questions like, “what does it mean to be whole in a world designed to fragment you? To have dignity when history has tried to erase your name?”

The search for that answer has taken us into the pews of the Black church, through the syncopated rhythms of jazz, and into the streets with clenched fists.

But sometimes we’ve also turned eastward. To Taoism. To Confucianism. To Chan Buddhism. And in those ancient Chinese traditions, we found a mirror. Not an identical reflection, but something better: a philosophical twin raised on a different continent.

The 19th-century Black activists who cited Confucius were being both performative and strategic. In an America that worshipped classical virtue while lynching Black bodies, quoting an Eastern sage was a quiet act of insurgency.

“You say you respect ancient wisdom?” they seemed to ask. “Then here’s Confucius, reminding you that benevolence and justice are the duties of the righteous.” That wasn’t mimicry. Rather it was martial arts with words. Philosophical judo.

W.E.B. Du Bois saw it too. When he visited China in 1959 and said, “China is flesh of your flesh and blood of your blood,” he wasn’t just pandering. He was tracing kinship, not through skin but through shared endurance.

Black folks and Chinese civilization had both suffered, both been underestimated, and both had the audacity to dream up their own heavens. Du Bois didn’t want to baptize China in Western religion because he knew they had their own gospel of endurance and moral clarity.

Fast forward to the Black Power era, and you see Mao’s Red Book in the hands of revolutionaries in Oakland. To some, it looked like mimicry. To others of us it was a revolutionary gospel, our own version of The Art of War.

The Black Panthers not only saw China as an ally but they saw in Maoist ideology a rugged code: self-reliance, communal discipline, the right to push back when cornered. Even if Marx was the seed, it was the Confucian-rooted moralism, the insistence on collective dignity, that made it resonate in Black communities across America.

But the most beautiful part of this East-meets-Black narrative might not be the speeches or manifestos. It might be the streets. The theaters in 1970s Harlem where Black kids cheered for Bruce Lee like he was one of their own. The dojos in South Side Chicago where Kung Fu masters taught discipline, breath, and the energy of qi to young men dodging bullets. The Kung Fu craze wasn’t just about kicks and flips. It was about reclaiming power from within. Taoist flow met the Black survival instinct, and something electric was born.

And then there’s RZA. If you want to talk about modern Taoist prophets in the Black community, you can’t skip the abbot of the Wu-Tang Clan. He didn’t just sample Kung Fu movies—he studied the Tao, practiced Chan meditation, and wrote The Tao of Wu like it was a streetwise Tao Te Ching.

He taught a generation of young Black listeners that the way of the Shaolin monk could live alongside the pain of the projects. That flow, balance, and spiritual discipline weren’t just abstract Eastern ideals but were survival strategies. Just like the blues. Just like the gospel.

But don’t get it twisted as this is no romanticized Orientalism. This is cultural synthesis. A deliberate borrowing, a remix in the finest tradition of hip-hop, where Black culture has always taken what the world discarded or misunderstood and alchemized it into soul.

Take meditation. Take stillness. For many of us, these weren’t foreign concepts. Our grandmothers called it praying on it. Our uncles called it cooling out.

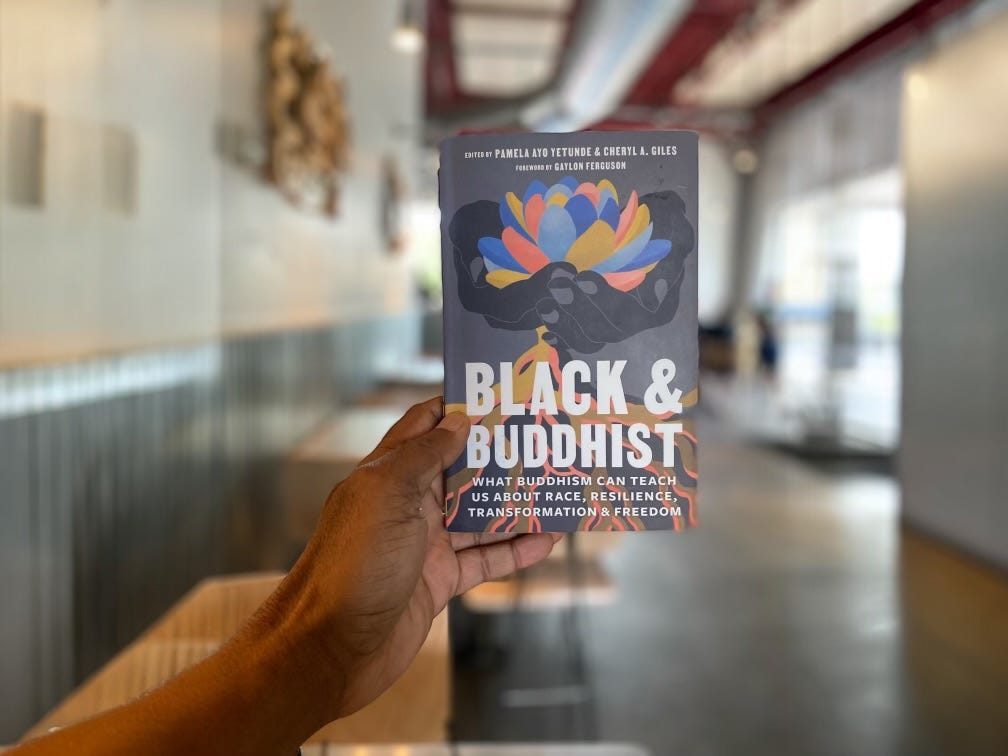

When Black Buddhists like Lama Rod Owens or angel Kyodo williams teach mindfulness today, they’re not “converting,” they’re remembering. They’re finding the silence that was always there beneath the noise of oppression.

Even the Taoist ideal of wu wei—non-forced action—makes sense in the Black American context. The Civil Rights Movement wasn’t about passivity. It was about pressure without panic. Think about Dr. King’s “soul force.” Think about John Lewis’ “good trouble.” That’s wu wei, y’all. That’s flowing around injustice like water around rock, until the rock gives way. Lao Tzu would have smiled at Selma.

And let’s talk about ancestors. Chinese Confucianism holds ancestor veneration as sacred. So do we Black folks. Whether it’s pouring libations, singing old spirituals, or speaking the names of the departed in prayer circles, Black Americans have long known that the past is not the past but prologue. It’s presence. It’s power.

In both traditions, the dead are never dead. They are the living wisdom that walks beside us.

So what do we make of this intersection—this strange, sacred dialogue between Black American soul and the Chinese mind?

We make art. We make philosophy. We make freedom.

Because in a world that wants to box us in, flatten us out, and pit cultures against each other, the Black–Chinese philosophical exchange says something radical, that liberation is polyphonic.

pol·y·phon·ic

/ˌpälēˈfänik/

producing many sounds simultaneously; many-voiced.

Freedom can wear many faces. And the Way, the Tao, is big enough to hold them all.

So I keep reading Lao Tzu. I keep listening to Wu-Tang. I light incense sometimes and sit still in the mornings. Not because I’m chasing some exotic spirituality. But because somewhere between the Mississippi Delta and the Yellow River, I found a path that makes sense.

A path that reminds me that even when I’m tired, even when the world is loud and unjust, I can still flow. Still endure. Still be.

And that’s the Way, isn’t it? The Tao. The ancestral current. The Black flame. The sacred river that runs through all things.

Even me.

Would you be kind enough to consider supporting full-time independent writers like me by subscribing today. Or, if you’re feeling generous in a small way, maybe you’ll wanna send a little (or a lot) of dirty chai latte love my direction. Every bit helps keep this Taoist journey flowing.

Hi Diamond-Michael,

What an interesting intersection.

I can't help but wonder how the working class might fit into this mix. I'm drawn to lots of things about black and eastern culture from within, not as a performative thing.

And I wonder if part of that connection I feel is about the similarity of experience between working class and those two cultures. I think seeking dignity and authenticity when the dominant culture other groups gives some shared perspectives.